The spectrum defines, divides and deciphers global politics. Despite accusations of being out-dated, and perhaps lacking in detail relevant to the present day, it remains the simplest way to understand complicated concepts, and truly grasp an often confusing world. It offers the visualisation of ideologies, creating a much easier way of comparing the relationships between various beliefs, ideas, and policies, whilst also allowing the plotting of major parties, politicians, and doctrines themselves. A greater level of comprehension is created by the spectrum when attempting to grasp the motives of a new policy or law- it also aids the detection of media bias, as well as even helping to reflect your own beliefs in a more concise way.

Changes throughout politics in the post-war era have led many to seek alternative forms of the spectrum, even leading to schools of thought suggesting it is no longer effective, or even viable. This will be developed below, however a shift from the more traditional economic way of perceiving variation in ideas (notably the famous communism-capitalism divide), to the idea of “open” vs “closed” beliefs (supported by the rise of ideologies focusing on cultural issues, such as feminism and ecologism), has begun to threaten the way we view and differentiate between various political creeds.

There’s even a debate surrounding the true method from which the linear spectrum is constructed, with the left/right divide usually being typified by varying attitudes to political change- despite this, some may argue that differing economic ideas should take centre stage. In a more modern world, attitudes shown towards equality have grown in prevalence when plotting ideologies on the scale, with socialists obviously advocating for it, liberals emphasising equal opportunity, but crucially not income, and conservatives generally seeing it as an impossible aim, whilst also stressing the importance of individualism. In this article, I will dive into the ins and outs of the modern-day political spectrum, discussing its various forms, interpretations, viability, and history, as well as the defining features of each section, including the ideologies that can be plotted on it.

Origins of the Spectrum

Many elements of modern day politics date back to the monumental French Revolution (including much of the socialist identity), and the left/right spectrum is one of them. In 1789, the French National Assembly met in Versailles. Throughout the several days of the meeting, the “radicals/commoners” with revolutionary views sat on the left, whilst the higher-status aristocrats/nobility who supported the monarchy, and therefore advocated against change, sat on the right. It doesn’t take a genius to spot the connection between this 18th century seating arrangement, and the modern-day political spectrum- quite literally, those who may be viewed as socialist today were on the left, and those who could be seen as conservative were on the right.

These connections helped establish a clear-cut, widespread association with the left and a desire for reform, as well as the right and more traditional, hierarchical ideas. The divide between attendees of the National Assembly in 1789 now highlights the divide that runs through political thought and action, after initially representing the choice between revolution and reaction. In the centuries that have followed, the spectrum has obviously diversified to keep up with a changing political world, with phrases such as “right-wing” and “far-left” having been used for decades now.

It has moved beyond a simple divide of left and right- it’s now common for a party on one side of the divide to have more in common with most on the other than many on its own. For some, attitudes towards revolution and change no longer represent the biggest criteria when forming the spectrum, with opinions on economics, and now issues surrounding culture and equality coming to the fore. Because of this, many have attempted to blend all of these aspects into a singular spectrum, or even change its very shape due to issues with the conventional linear structure.

Forms of the spectrum

Linear

When most people think of the spectrum, they think of its linear variant. It’s been a staple of politics for decades, and as said in the introduction, despite being simple and a little outdated, it can define and divide the topic, whilst also explaining parties, politicians, and ideologies in a straightforward way.

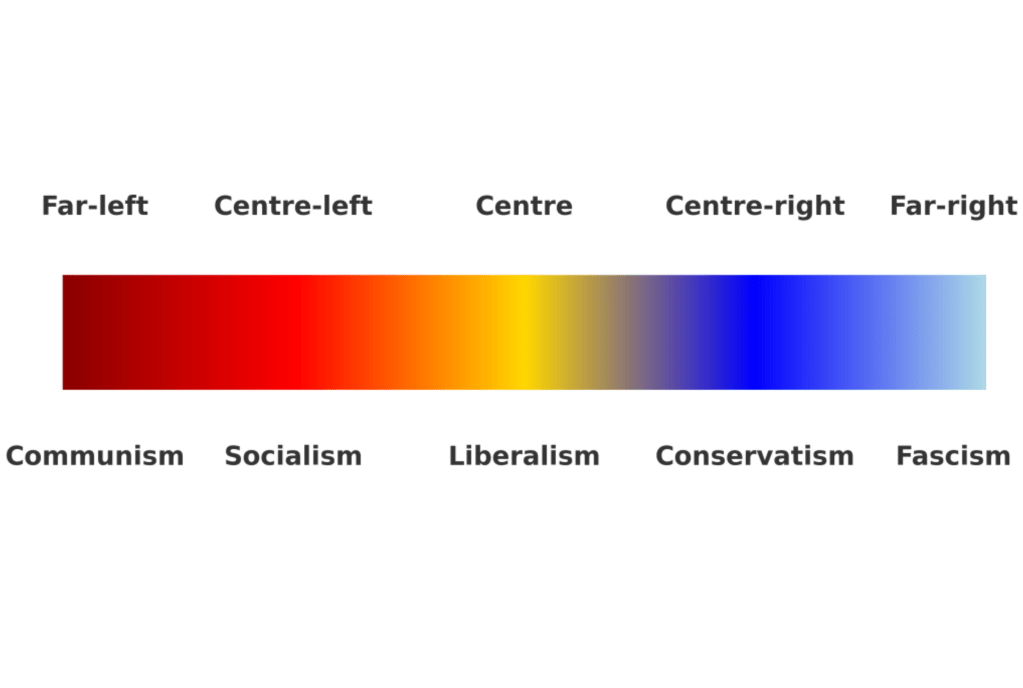

As suggested by its name, the linear spectrum consists of a singular axis, with left and right generally considered as its poles. This enables people to use phraseology such as “centre-left” and “far-right”. When drawing out the spectrum from left to right, it is standard to list “far-left”, “centre-left”, “centre”, “centre-right” and “far-right” either on top or bottom- this conveniently means that the distinct ideologies of communism, socialism, liberalism, conservatism and fascism can be listed (in that order for correspondence). This will be discussed in further detail later on, however there are multiple factors contributing to how the linear spectrum is constructed, and therefore where subjects are plotted onto it. Historically, it is a mixture of factors including attitude to change, economic stance, and view on equality, with the influence of cultural issues rising, even threatening the linear form’s viability.

Additionally, some idelogies actually straggle differing parts of the spectrum. Anarchism, for example, is generally seen as being far-left, however its national variant is far-right due to views on racial seperatism and nationalism. Other ideologies can mean different things across the world- in Europe, populism predominantly focuses on issues such as immigration, making it distinctly far-right, whilst in South America, it has historically been linked to more leftist state interventionalist economic policies. Despite its convenience, the simplicity of the linear spectrum also leads it to have drawbacks, especially as politics change through time, which has led some to seek alternative revisions of the scale.

Horseshoe

One of these problems was truly pointed out in the Cold War period. It was often highlighted that ideologies towards the far ends of the linear spectrum actually had more in common with each other than those closer in the centre- it was claimed that fascism and communism resembled each other by a shared tendency towards totalitarianism.

The solution to this is bending the line of the linear spectrum to create a horseshoe. This means that the centre (generally liberalism) is at the bottom, furthest away from both extreme ends vertically. The centre-left and centre-right, or socialism and conservatism, are far apart horizontally, but still close to the centre (they’re not extreme ideologies). At the top of the horseshoe sit fascism and communism, the extreme versions of left and right. Their proximity to each other in terms of positioning represents their shared totalitarianist tendencies, however they actually never touch, showing how they are still very different views of how a nation should be ruled.

On the surface, the only way the horseshoe spectrum appears lesser than the linear is slightly less simplicity, however it has also been accused of oversimplifying ideologies, and focussing on the extreme ends a little too much. Perhaps the biggest criticism of both the linear and horseshoe spectrums is that they remain one-dimensional- something that its third form aims to combat.

Two-Dimensional

As time goes on, there are more and more accusations of the linear spectrum being outdated, due to the diversification of political issues, and in some cases, change in focus. Many of the “new” ideologies such as feminism, ecologism and fundamentalism focus on cultural issues rather than economic ones, or attitude towards change. Additionally, the lack of more historic factors including liberty and authority add to the feeling that a one-dimensional spectrum is simplistic, generalised, and lacking.

The addition of a vertical axis with authoritarian at the top and libertarian at the bottom has led many to name this scale the “political compass”. When plotting parties, it gives a much more diverse view of its character and policies. Admittedly, the more historically dominant extreme ideologies are often authoritarian (take fascism and communism), however anarchists may disagree with that statement. A second dimension reveals many aspects that the linear spectrum may hide- for example, it would be acceptable to state that Labour are closer in pure distance to the Conservatives than the Green Party on the compass. You probably wouldn’t say that when plotting each by one-dimension. It goes without saying that some may choose to interchange authoritarian/libertarian with another measure- perhaps one that involves newer cultural-issue oriented ideologies a little more.

When compared to the linear and horseshoe spectrums, it becomes obvious that the further level of detail offered by “the compass” makes it a better option, however it’s unlikely that it will gain the same prominence, mostly due to pure phraseology. I personally believe that the way the simple left/right scale is ingrained into our vocabulary means that the linear spectrum will always prevail. It goes without saying that the entire political spectrum itself may see a dip in usage due to a changing climate, which will be discussed later in the article.

What each part of the linear spectrum means

Left versus Right

The left versus right debate is the biggest in politics. You can see this by just looking at the most historically significant parties in major nations around the world- Conservatives and Labour in post-WW1 Britain; the CDU/CSU and the SPD in Germany; the PP and the PSOE in Spain; the Republicans and the Democrats in the United States. The common theme here is that one of the parties who are constantly fighting for power are left, and the other is right. Left or right is the basis when comparing varying political ideas, with each side sharing distinct characteristics and viewpoints.

The left grew from a desire for change, often even revolution, which is shown through its French Revolution origins. It has constantly served as the attacker of the conventional, and the opposite to Conservative thought about the preservation of tradition and normality. Socialism is the biggest left-sided ideology, and it forms the basis of left ideas surrounding equality. This side of the spectrum has always advocated for equality within a nation’s population, and greater support for its working class. Egalitarianism is a key cornerstone of the left, which is the principle that all people are equal, and therefore deserve equal rights and opportunities. A belief in government intervention is also something a lot more common with leftist parties, meaning that the ruling body of the state is permitted to interfere with the free market, and influence or alter its outcomes.

The right has generally sought to defend the present order, tradition, and conventional from the “threat” of change- this was where division between it and the left began. Most ideologies sitting on the right see widespread equality as unachievable, or even undesirable- a key aspect of Conservatism is the belief that hierarchy holds great importance. As much as most centre-left parties are still capitalist, the right is seen as being far more capitalist than the left side of the spectrum.

There’s a strong belief in the free market, and the idea of unrestricted competition between privately owned businesses, whilst limited government is also a key pillar of most right-sided ideologies, where the power of the state is restricted by law (usually a constitution). The Brothers of Italy party have recently shown the importance of tradition in most right viewpoints- this can often create hardline stances on issues such as immigration. Much of the right believes that tradition is important due to the fact that it creates a well-known structure, therefore giving people a stronger sense of belonging. Additionally, conservatives will often point to the fact that for it to have lasted so long, then it must be good.

Ideologies on the spectrum

Communism

Communism is a perfect example of the far-left. This political and economic doctrine aims to create a society centered on common ownership, where a profit-based economy is replaced with communal/state control over at least the major industries of production. It is generally seen as an ideology in its own right, despite falling under the larger umbrella of socialism- Marx even used them interchangeably. Communism’s attitude towards equality epitomises extreme left beliefs- in communist states, there is a classless society, meaning that there is no working class altogether. Despite the fact that the population carry out jobs of differing importance and difficulty, they are still seen the same- it’s the ultimate implementation of egalitarianism.

Socialism

Socialism is a firmly typical left ideology. In many ways, the two words are interchangeable to a relatively high degree. The term socialist itself comes from the Latin “sociare”, which means to divide or share, summing up the key aims of the doctrine pretty well.It has traditionally been defined by its role as opposition to capitalism, seeking to offer a “more humane” option.

A desire for social equality has been the biggest driving force of the creed throughout history, with the idea of society being a collective body rather than a collection of self-minded individuals. Traditional Marxist ideas of socialism (arguably stemming from again, the French Revolution) support the use of revolution as means of establishing a socialist society, whilst more modern, closer to centre social democrats support a more gradual approach. Weaker versions of communist ideas surrounding land ownership and industrial production are still key pillars of the ideology.

Liberalism

The debate over where liberalism sits on the spectrum is a little hotter than with socialism and conservatism, with people often arguing that instead of a more simple position, it is clearly left-leaning enough to be recognised as so (take the UKs Liberal Democrats for example). Again, the Latin origins of Liberalism’s name well-explain the ideology- “liber” means free men (effectively those who aren’t serfs or slaves). The doctrine has often been called “the ideology of the West”, due to ideas surrounding individuality and freedom.

The central theme of the creed is the idea of creating a society where individuals can satisfy their own interests, and search for fulfillment- they believe that all humans should have the freedom to make their own choices. Despite this, liberals also believe that rules must be put in place to protect individuals, therefore society should be politically organised around the two principles of constitutionalism and consent. In many ways, especially with its capitalist ideas, Liberalism reflects the typical values of the United States almost perfectly.

Conservatism

If socialism is the ideology of the left, then you could certainly say that conservatism is the ideology of the right. The name of this doctrine doesn’t have the Latin roots of the two other big three political creeds, however the meanings of the word conservatism still go a long way in explaining the ideology. It can refer to cautious or moderate behaviour, a conventional lifestyle, a fear of/refusal to accept change, particularly shown through the verb “to conserve”.

Throughout history, Conservatives have been the defenders of the status quo, with the belief that the established society offers individuals the sense of belonging they need, as well as offering a sense of stability. These tendencies also support the upholding of tradition, and the structure of society. Followers of this ideology believe that hierarchy is a must in a functional society, whilst seeing true equality as an unachievable, or even undesirable, far off aim. Similarly to liberalism, Conservatism is a huge advocate for the free market and individual liberty, as well as limited government.

Fascism

Fascism’s position as the most extreme version of the right means that it has been the ideology of some of the world’s most awful and evil regimes. Fortunately however, the doctrine appears almost dead in the developed world (there has been a rise popularity for far-wing parties throughout Europe, but the likes of Reform and the AfD are thankfully still a way of fascism). The bundle of sticks analogy was used by Italian dictator Benito Mussolini, and it describes the beliefs of the ideology pretty well- you can easily break one of the sticks, yet when many are tied together, you can’t.

Fascism believes in strength through unity, however the way dictators often seek to create this is through the creation of an “ideal race”. Values such as rationalism, progress, freedom and equality are overturned in the name of struggle, leadership, power and war, creating a strong anti-character throughout the ideology (it is anti-liberal, anti-socialist, anti-capitalist etc). Fascism is by far one of the most authoritarian ideologies, with its ideas often requiring a strong dictator to be put across- many fascist states (as with communist, the other extreme ideology) are one-party nations.

“Open” VS “Closed” politics- the end of the spectrum?

There’s a rapidly growing school of thought suggesting that globilisation could be slowly making the political spectrum less and less viable. The emergence of an interdependent and interconnected world has seen the rise of “open” and “closed” political attitudes- many believe they could replace left and right. Those who are open usually favour globilisation, synthesize with an inclusive view of national identity, therefore being tolerant of or welcoming cultural diversity, and typically support liberal social values and norms. In contrast, people with “closed” thinking usually are either suspicious of, or oppose globilisation altogether, fear cultural diversity, so are drawn to a greater sense of nationalism and exclusive cultural identity, and generally support conservative values and norms.

This deeper focus on cultural issues no doubt supports the inclusion of the “new” ideologies (feminism, ecologism etc) a lot better than the traditional left/right divide, however I still believe that the argument of open/closed replacing the conventional spectrum is a little short-sighted. First of all, you could argue that “open” is more than loosely similar to many leftist views, with the same going for “closed” and the right. Second, open/closed may be more tailored to modern ideas, however it is also largely limited to them, with a deeper view of economic issues being lacking. In my opinion, despite being a little outdated and lacking, the traditional, simplistic linear spectrum will prevail.

In many ways, its under-complicatedness plays to its advantage, and the one-axis structure means that you can combine multiple factors including economics, attitude towards equality, cultural issues, and degree of authoritarianism onto one scale, where you can plot parties, politicians, and ideologies themselves. Finally, the way that phraseology such as “left-wing” and “centre-right” is purely ingrained into our vocabulary means that I believe that the linear spectrum will remain as politics’ main scale for years to come.

Thanks for reading my latest blog post on Your World Explored by me, Lewis Defraine. Feel free to offer your support, or even constructive criticism in the comments section below. A like would be greatly appreciated, and if you’d like to receive more articles from Your World Explored, you can also subscribe. Also, you can take part in the poll down below.

Key sources-

Political Ideologies- An Introduction- Andrew Heywood

https://www.britannica.com/topic/political-spectrum

https://www.unifrog.org/know-how/understanding-the-political-spectrum

Leave a comment